By Barry Morrison

Roseline Delisle Capsule:

- Dates: 1952-2003

- Production Dates: 1972-2003

- Locations: 1973-77, Gaspé Peninsula, QC; 1978-2003 Venice and Santa Monica, California

- Types of Work: early functional; Postmodern sculptural

- Preferred Kiln Type and Firing Process: most likely an electric kiln and oxidation firing.

- Preferred Clay: earlier stoneware then porcelain; and later earthenware

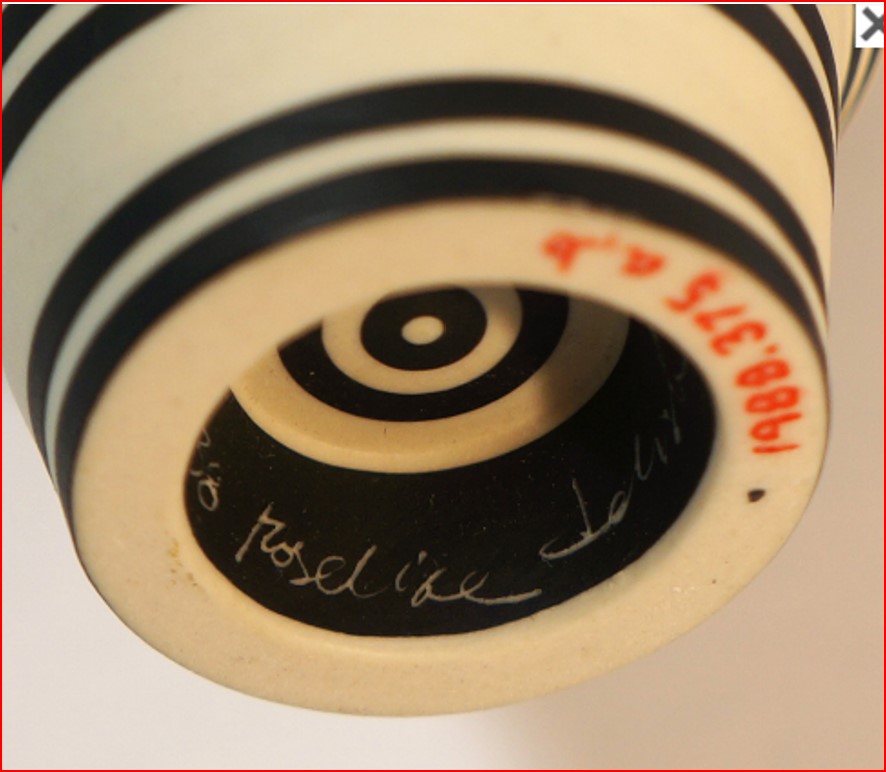

- Signature/Mark/Chop: Delisle would sign her works usually discretely “hidden” and scratched into the base of component elements, frequently listing the name of the work or component and a date.

- Even her signature and other details scratched into a hidden surface as seen below show the precision of her style.

Biography:

One of the joys of having a website is that others can suggest artists to write about. Enid Legros-Wise suggested a page on Roseline Delisle who had apprenticed with Enid for a while. Delisle was an artist about whom I had thought writing but did not know where to start. Thank you for helping me focus Edith.

Roseline Delisle was a Quebec-born artist whose career and art reached their heights not in Quebec but in the heady California ceramic scene of the 1980s and ‘90s. Although she always retained Quebec as her source, Santa Monica, California, would be her creative place and a space for starting her family.

Roseline Delisle was born in 1952 in Rimouski, Quebec, on the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River, just over 300 kilometres northeast of Quebec City. Born into a creative family, her mother a part-time clay sculptor and her father, a wood carver, gave her a headstart. 6

Initially her educational interests, via her brother, were in the science field, physics and chemistry, but a visit to the art school, l’Institut des Arts appliqués, in Montreal in 1969 was all it took to set her on her ultimate career path.6 Although trained in multiple art disciplines at the school, ceramics was the medium that captured her attention. There she focused on ceramic industrial production.10 Yet I think that the early science interest was an underlying force field in her ultimate style, in her precision of forms and surfaces.

Roseline explains her shift to ceramics after visit to the Montreal Institute:

“I was fascinated by the wheels, the kilns, the personality of these ceramic artists.” 8

Interestingly Delisle’s biographies from various sources do not indicate any later formal studies, except one: a Fire+Earth Catalogue includes a 1981-82 listing with no details: “studies at Santa Monica City College.”9

After graduating from the four year Montréal programme (1969-73), and wanting to learn more about working with porcelain,2 Roseline apprenticed with Enid Legros-Wise from June 1973 in the Gaspé region, selling and exhibiting – along with exhibition rejections – until December 1973.

Enid comments on this early phase of Roseline’s career:

“Roseline must have worked for me from the end of June 1973 until we packed up and took everything to Montréal to do the Salon des Métiers d’art du Québec show in December of that year. She was a dedicated worker and her attention to detail fitted very well with my own style and requirements. She was reliable and it was a pleasure to have her around. … Following the SMAQ show I did not need her help, and she quickly began working on her own, producing carefully thrown and finished functional/decorative objects. … She exhibited in the Salon des Métiers d’Art du Québec also … .1

Enid comments on further developments in Roseline’s career progress:

“At some point during this period I had volunteered to organize a pottery club. I managed to convince the local school board to invest in wheels and other equipment and eventually persuaded them to add a gas kiln. I also persuaded them to hire Roseline and a potter Roseline knew … to build it.”1

However, this phase was not to last long. Roseline did set up a studio in the Gaspé but found the cold climate, isolation, and lack of running water and electricity not to her liking. Sales in Montreal were meager. She was increasingly in debt and would refer to this phase of her career as her “granola years.” A period with friends did not help her financial situation and in 1977 only a stint as a lumberjack in Alberta helped her.6

Penny Smith describes this phase, of her grit and determination, giving colour to Delisle’s personality:

“As French Canadians – Delisle spoke no English at this time – the group was given one of the toughest assignments with the most basic of camps. However, Delisle’s childhood experience of family summer house building with her father, saw her shouldering her chainsaw with the best of them and, despite her slight frame, she endured sub-zero temperatures to make enough, in a matter of months, to repay her debts and enable her to move on.” 6

Friends encouraged her to move to warmer climes in California. She made the move in 1978, setting up a studio in Venice, California.

Initially limited by a six month visa Delisle set herself up with a wheel and kiln for $50 a month. She spoke no English but put up a sign in the window “Studio Open” and sold “petits pots, tout simples.” 8 She moved her studio to Santa Monica, eventually catching the eye of people such as Garth Clark. Personal success followed with her establishing a family. 6

“[E]n 1978, je suis partie à Venice, en Californie. Sans le savoir vraiment, peut-être par instinct, je me retrouvais à Los Angeles, la ville qui fut le berceau de la céramique d’art avec des précurseurs comme Peter Voulkos, John Mason ou Ken Price.” 8

(“[I]n 1978, I left for Venice, California. Without really knowing it, perhaps instinct, I found myself in Los Angeles, the city that was the birthplace of art ceramics with precursors like Peter Voulkos, John

Mason or Ken Price.”)

In her resumé Delisle was reticent about mentioning that she conducted workshops. She made occasional trips back to Quebec, probably mostly for family reasons, but would sometimes conduct workshops. Paul Mathieu 20 and Danielle Turgeon 8 mention talking with her at such events in Montréal.

What New York was to the art scene, the the West Coast was the dynamic centre for ceramics. Positioned in the Los Angeles area, even by osmosis she was well located to to be influenced by major ceramic artists, to experience trends, and to attend cultural events: artists such as Peter Voulkos, Ken Price and Lucie Rie; schools such as Otis and Davis; and to attend international cultural events, interestingly, from Europe’s Modernist period of the 1920s and ’30s. She was inspired in 1979 by the Bauhaus’ Oskar Schlemmer’s 1922 Triadic Ballet at the University of California at Los Angeles, and the Kazimir Malevich Russian Constructivist/Suprematist exhibition at the Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center, Los Angeles, in 1990. 6

In short, for a ceramist, California was THE place to be with artists establishing new norms, forms and directions in the clay medium. Her inspirational sources thus cut across personalities, decades and continents. A far cry from the Gaspé.

Eventually she was able to stay permanently but for several years would return to Quebec to sell, and to exhibit at the Canadian Guild of Crafts and Toronto. But she always returned to Venice. 8

Delisle mentions a key step in her exhibiting career. People began to hear of her. Unfortunately she was thin on recalling details as to dates and names: e.g. “someone”, “a contemporary art gallery in New York”, but no exhibition date:

“Lorsque je lui ai téléphoné, elle préparait un vernissage. Je lui ai dit que je n’avais que quelques pièces à lui montrer, que ce ne serait pas long. J’y suis allée et elle a exposé mes plats quelques jours plus tard. Ils ont tous été vendus. J’ai eu mon exposition à la galerie peu de temps après et le catalogue s’est retrouvé au Japon, où j’ai ensuite exposé trois fois.” 8

(“When I called her, she was preparing a vernissage. I told her I only had a few pieces to show her that it wouldn’t take long. I went there and she displayed my dishes a few days later. They were all sold. I had my exhibition at the gallery shortly after and the catalogue ended up in Japan, where I then exhibited three times.”)

Her work further caught the eye of more California and New York galleries, and inevitably international collectors and museums.

Delisle was quite open about the reality behind the “glamour” of gallery success and sales – and family – while working in the studio, an old garage in Santa Monica :

“Nous sommes très organisés, nous faisons presque du neuf à cinq ! C’est ça la vie d’artistes avec un enfant !” 8

(“We are very organised. We are almost doing nine to five! That’s right the life of artists with a child! )

But she was also a self-acknowleged pragmatist:

“La vente est mon moyen de survie, ce n’est pas très romantique. Après une exposition, je reviens à l’atelier et il faut tout reprendre à zéro, trouver de nouvelles inspirations, expérimenter.” 8

(“Selling is my means of survival, it’s not very romantic. After an exhibition, I come back to the workshop and you have to start from scratch, find new Inspirations, experiments.” )

From Rimouski to Los Angeles Roseline Delisle left her mark on the contemporary Ceramic scene. Although she spent most of her career in the United States her basic identity was always listed as Canadian in international exhibition catalogues and publications.

Active right up to the end of her life, Roseline Delisle’s career was sadly cut short. She died in 2003 of ovarian cancer.

A Roseline Delisle Gallery

To begin, a few words on Delisle’s work in general, and a nod to two key articles on Delisle, her life and her work:

- Paul Mathieu’s extensive 1992 profile of Delisle’s methods and aesthetics in the spring issue of the Alberta Potters’ Association publication, Contact 20 is a must read.

- Penny Smith on Roseline Delisle in Ceramics Today 6, a Reprint from Ceramic, Art and Perception, gives many personal on Delisle’s art and life, especially her early years.

- Delisle from the her early years visualizes her works in profile.

- Her colours are winter colours, blue, black, white. But I could not find any reference to symbolic a use of colour.

- Titles of works indicate the number of “separate” pieces or elements that make up a work: e.g quadruple, tryptich, etc.

- Delisle uses only line for “decoration”, not pictorial illustrations.

- Her work is far from the Leach tradition but touches on the “industrial” Quebec teachings from her early Montréal days.

- Mark Delvecchio describes her work as “simplified, sharp, linear, outlines and flat planes of colour” 5

Roseline Delisle: Very Early Work:

Delisle’s earliest works naturally show the influence of her studies in Montréal. In short, the practicality of functional design.

Much of her work in these early days would have been in stoneware but she soon became familiar with porcelain, a clay that would be a prime medium for much of, but not all of, her career. Later, in the early ’90s, as her works became larger, to avoid the sometimes quirky effects of porcelain and achieve some of her effects and forms, she shifted to earthenware clay.

Enid Legros-Wise comments on Roseline’s earliest work:

“I especially remember the porcelain bowls with the charming line drawings circling them as decoration. … Bowls, lamps, and goblets that could be turned upside down to become candle stick holders. … We can see in these pieces a hint of the horizontal lines and the whirling top silhouettes of her later sculptures.” 1 …

Enid further comments that Roseline was skilled using line:

…Roseline was also very talented on paper; she could sweep a line across a page creating a beautiful composition with almost nothing.” 1

Line was an important feature of Delisle’s work. She would create precise drawings of her planned work, as seen in the above photo

Penny Smith comments:

Her designs, … are initially mapped out mathematically, cut and dissected geometric shapes that are reassembled into strong graphic profiles. These initial drawings she uses as guides to work out the actual size and shape of the pieces she is to throw, to calculate how the piece will finally go together. Later, as a relief to the strictness required of her making techniques, and as a prelude to the exacting task of decorating, she will return to the drawings, re-rendering them in energetic expressions of rapid marks that make them start to shimmer and move.” 6

Delisle would continue “simple” forms and designs several years after her move south. But this 1983 bowl reveals aspects of her later work: her favoured colour scheme of white, blue and black, here encircling the extremites of lip and foot, and a matching linear banding in the interior.

Why just three colours? Perhaps for the purity of porcelain; or just the establishment of a signature colour scheme. She developed a focus on surface, form, silhouettes and outlines, without the distractions of potential image associations or other graphic effects produced by colours.

Six years later she was creating fine, thin works, here a porcelain Blue Bowl in her signature blue with a fine line of white on the rim and foot

There would be hints of a Picasso-inspired playing with form, so that a bowl becomes more than a bowl; an element that if turned upside down becomes a lid of something greater as in the top of Quadruple from her Black Series.

Quadruple shows the development of form-shifting and additions that would become a characteristic of one of her more famous styles. Thin white lines define elements and junctures, the whole capped by a white lotus-like finial.

Yet overall there is a purity of form and colour. This is not “messy” clay or Modernist “truth to materials” in a minimalist form; rather there is almost an industrial, machine precision in form, line, surface and colour, all created on the wheel.

The Frank Lloyd Gallery offers a summary of Delisle’s work and style:

“Meticulous in their fabrication and decoration, Delisle’s nonfunctional vessels are elegant and precise. The geometric rigor of her pieces is offset by their often anthropomorphic proportions, and richly satisfying surface qualities.” 4

Explorations would continue further in modifications of the basic functional form. Here in Footed Cup a basic shallow bowl- with what appears to be multiple blue and white lips surmounts a stack of smaller plate like discs on an inverted truncated cone. Each defined, separated, by a ring of white.

The colours and lines are both precise and uniform, a characteristic of her work; the surfaces are smooth and complete, total coverage evenly applied.

Viewing Delisle’s work is a two step process: from a distance they stand (especially the larger works) as 2D silhouetters. It is on approaching them that the 3D form becomes clearer: a dimensional transition, a shift from from 2D symmetry to a full 3D and 360° symmetry. There is a constant inter-dimensional play: one dimensional lines; two dimensional surfaces; and three dimensional forms.

Kristine McKenna notes how Delisle thus creates “oppositions”:

“As aesthetic forms, they’re structured around a number of oppositions: profile versus surface; vertical thrust versus horizontal stripe; order versus whimsy; color versus form. Perhaps most important, what they do is take another opposition — art versus craft — and skewer it with wit and shocking grace.” 16

Roseline Delisle. Porcelain Vessel With Stripes. (Four Views) c. 1988. Signed. Ht. 20.32 cm, Dia. 9.53 cm. Provenance: Garth Clark Gallery. Estate of Annette McGuire Cravens, Buffalo, NY.

While developing the complexity of her forms Delisle would also play with interior and exterior contrasts and “surprises”. What often looks like a simple, lidded, closed, functional vase upon closer inspection is more complex; and this complexity would increase over the years. Appreciation of her work could become almost a game, a puzzle. What you see on first glance, although eye-catching, is only the beginning. Porcelain Vessel With Stripes above at first looks like a hypnotically banded, lidded vase. The ridges near the base are subtle, almost overlooked at first. The eye is first captured by the multitude of bands of black and white, and the flaring dish-like discs at the shoulder. The cone top with similar banding to the body is topped by a small finial, a handle. The top cone is a bowl-like lid, but blue inside, like the vase body interior itself. There is an element of playful puzzle surprise here, but all done with immaculate precision. And in only three colours!

But this complexity implies an unintended “exclusivity” in what can be seen or appreciated by the museum/gallery viewer: handling or opening the works to reveal further details is limited to a few, owner-collectors, gallery and museum staff and the like. Her works are not displayed with this openness.

But how does she make these works? Paul Mathieu in his detailed profile of Delisle describes steps of her porcelain process that only a fellow-ceramist, one whose hands have been in the clay, can identify. I quote at length here:

“All steps are actually performed at the, wheel: succinctly, the pieces are thrown, in section, trimmed, turned and polished, banded, painted and after firing, waxed. In Roseline’s work, the wheel as a universal tool has attained proportion of an obsession. …The pieces are thrown rather thick, yet as thin as possible, to prevent cracks caused by insufficiently compressed clay. … Over the next months, these sections will be progresively trimmed in order to thin the walls carve the the finials and the ‘fins … Each piece will then be polished inside and out, with a small stone, while slowly spinning on the wheel. Once perfectly dried, the pieces are painted with slips, mostly black and a luminous blue. … The smoothness of the finely ballmilled slip is similar to the tightness of the smooth, vitrified white porcelain clay. The pieces are banded in a variety of patterns, inside, as well as outside each section, and the black slip is painted on all surfaces that fit together, where a permanent bond is required. The slip will vitrify in the firing, thus joining the two sections. … Each piece will then be polished inside and out, with a small stone, while slowly spinning on the wheel. Once perfectly dried, the pieces are painted with slips, mostly black and a luminous blue. The smoothness of the finely ballmilled slip is similar to the tightness of the smooth, vitrified white porcelain clay. The pieces are banded in a variety of patterns, inside. as well as outside each section, and the black slip is painted on all surfaces that fit together, where a permanent bond is required. The slip will vitrify in the firing, thus joining the two sections. Over the next months, these sections will be progresively trimmed in order to thin the walls carve the the finials and the ‘fins’. … After a single firing, the pieces are sanded smooth under water with fine sandpaper, then dried. … [I]n order to accentuate the vividness of the colours and the silkiness of the porcelain, the pieces are waxed with a mixture of beeswax diluted in turpentine.” 20

Sculptures Part 1: People and Family Sculptures

Her later works, especially, are a play between line and plane, silhouette and volume, with a new emphasis on content that suggest gender and relationship..

Her works are still “clean” with colour boundaries, and sharp, precise edges. But all done on a potter’s wheel.

The sense of touch in her “functional” ceramics is reduced in favour of sight. In some cases because of the surface some of her works’ are so smooth and uniform there is a potential hesitancy in leaving finger marks. Some shapes imply “vulnerability” with sharp edges and contours.

However, since her works must inevitably be handled, by museums, auction houses or owners she would protect the surfaces as described by Penny Smith:

“As in her earlier work, decoration still comprises banding coloured slips (with a little added gum to harden the colours during handling in kiln packing) on to the burnished leather-hard pots while they revolve quickly on the wheel. This she does by eye with pinpoint accuracy and a steady hand, to achieve the calculated negative spaces between the coloured stripes.” 6

Her signature styles developed a general closed form appearance, of stacked cones on cones, of cone-vase quasi-functional forms, of stacked discs/dishes, and with the addition of finials. This was a move into sculpture that overrode any practical functional usage. Interior decorative colouring, also prevented their practical, functional use. In short, although she remained true to working on the wheel, she played with Modernism on her own terms. She was Postmodern.

A natural development of her interests developed from using the traditional “body”language of pottery into her developing sculptures as people. This is particularly noticeable after the birth of her daughter Lilli in 1993. Size would also become a new element.

Penny Smith describes Delisle’s using her basic forms to increase the scale and stability of her works:

“… inverting and stacking together pieces as a natural way to achieve larger scale, and increasing their precariousness by introducing impossible bases…” 6

Creating large vertical forms required, however, a new element, a hidden one in her work. Her new designs required a stability in the earth-quake prone Los Angeles region. For such narrow, vertical works a metal rod had to be inserted in the design and and incorporating a heavier sand-filled base for further stability,

Delisle comments on the the scope and scale of her production of sculptures, some measuring seven feet (2.1 metres), still with her favoured three colours.8

“Techniquement, il faut être très précis … On jurerait que la sculpture a été faite en une seule pièce, mais elle en compte parfois une dizaine.” 8

(“Technically, you have to be very precise … one could swear that the sculpture was made in one piece, but sometimes it has around ten.”)

Purchased with funds provided by Friends of Clay

and Decorative Arts Council. Photo: collections.lacma.org

With advances in her technique, clay change, and confidence Delisle was able to create larger and more complex forms. The three images above have been “scaled” to approximate the variety of sizes of her production.

“My work operates on the vertical because I think of the pieces as people. When I throw I often feel that I’m allowing a form to materialise, rather than forcing one into existence. Even though every piece begins with a highly precise drawing, I find it easy to let go of preconceived ideas and just throw.” 15

Sculptures Part 2: Dancer Sculptures and Spinning Tops

Her latest works from a distance look as if lathe-turned, a natural consequence though of her use of the wheel. All her work, form and design, is wheel-based.

Such works suggest simple but precise forms, almost mechanical in precision, using the wheel movement for shape and line, precisely measured and placed in a delicate balance like a ballet dancer, but fluid, poised to make the next step. Adding to the complexity and potential fragility was the use of extended finials

But the increase in scale came with a price. The quirks of dealing with high-firing porcelain on larger multi-form works prompted Delisle to start using earthenware in her larger works. The Frank Lloyd Gallery comments:

“Although most of her early work was made in the demanding medium of fired porcelain, Delisle turned to an earthenware clay body to accommodate her desire to build larger scale figurative pieces. Her largest works are composed of several pieces, which stack together seamlessly. The work was formed and decorated on the wheel, the fundamental basis of Delisle’s practice. Horizontal striping in black, white, and blue both accentuates and disrupts the smooth proportions of her wheel-thrown forms.” 4

Increasingly Delisle would use elements that coming from the wheel become truncated cone elements. Sometimes these are stacked. Later she would stack elements as circular pyramids.

Delisle states she conceives of her works:

“My work evolves from the concept of the unity of opposites. … Black and white, strength and fragility, movement and stillness. I conceive the pieces in profile. As constructions of triangular moments.” 17

Overall there is a purity of form and colour. This is not truth to materials in a minimalist form; rather, there is almost an industrial, machine-like precision to form, line, surface and colour.

Her colour is abstract, either broadly defining and separating elements, or precisely hand-laid on a rotating surface, energizing either a flat disc or a coloured interior.

McKenna further comments on her latest works:

“Evocative of stylized harlequin figures that threaten to morph into spinning tops, the work is at once whimsical and austere, and it feels futuristic in an old fashioned sense.” 16

Such works push their stability to the limit, exploiting the visual interplay of height, depth, expansion and contraction like multiple versions of the Big Bang.

There is a certain postmodern irony with hints of Delisle’s long time interest in early twentieth century Modernism, especially the influence from the Bauhaus, and particularly artist/teacher Oskar Schemmer’s, costume stripes and movement.

Kristine Mckenna, in the Los Angeles Times adds further impressions of these latest works:

“Delisle’s work has the delicacy, intricate detail and impeccable craftsmanship of a Faberge egg, … Evocative of stylized harlequin figures that threaten to morph into spinning tops, the work is at once whimsical and austere, and it feels futuristic in an old-fashioned sense.” 16

But there is a need to describe a further aspect of Delisle’s works. She achieves these “industrially” precise, geometric forms, designs and decoration through extensive craftsmanship, attention to precision and detail to, surface, colour, finish, and total effect. In fact when dismantling these works for transport or storage there is a sense of “Aha, that’s how it works”, of the secrets of a magician’s illusion. The magic is more important than the reality; a bit like taking a machine apart to check its sprockets and gears, pistons and struts. Yet as such work is dismantled it displays a constant series of visual surprises from the decorated interiors.

Roseline Delisle. 2001. Octet 4. Earthenware. Height 66.0 cm, Outside Diameter 27.0 cm; Photo: historymuseum.ca

Perhaps because of her migration to warmer climes Roseline Delisle is lesser known in Canada than on the broader world stage. Yet she maintained her Canadian roots while exploring what the world had to offer. She identified her signature style and technique, truths to her artistry in a distinctive style. Although her ultimate forms may be sculptural her techniques were purely ceramic: clay wheel and kiln .

“It never occurred to me that my career would last this long, but I was recently struck by the fact that I’ve spent the last 29 years perfecting a specific idea. When I ask myself how I’ve stayed with it for so long, I remember a dream I had many years ago. I dreamed I was walking down a long road and that the road was my work. The sun was setting at the end of the road, and all I had to do to get to this exquisite sunset was keep walking.” 16

A Select List Museum Collections

- Aichi Prefectural Ceramic Museum, Seto, Japan

- Arizona State University Museum, Tempe, Arizona

- The Canadian Museum of History, Gatineau, Québec

- Charles A. Wustum Museum of Fine Arts, Racine, Wisconsin

- Cincinnati Museum of Arts, Cincinnati, Ohio

- Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York

- Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan

- Everson Museum of Arts, Syracuse, New York

- Getty Center for the History of Art and Humanities, Brentwood, California

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Montréal, Canada

- Musée des Beaux Arts, Montréal, Canada

- Musée du Québec, Québec, Canada

- Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California

- Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan

Endnotes & Bibliography:

1. Enid Legros. Email and Facebook correspondence, 24/07/2020 ff.

2. Jefferies, Susan. A PLACE IN CERAMIC HISTORY: Roseline Delisle and Walter Ostrom.” Crafting New Traditions: Canadian Innovators and Influences, edited by Melanie Egan et al., University of Ottawa Press, 2008, pp. 25–29.

4. Frank Lloyd Gallery. Pasadena, CA. Various online catalogues involving Roseline Delisle’s works.

5. Mark Del Delvecchio. Post Modern Ceramics. 2001. Thames and Hudson, NY. pp. 28, 32, 195-6.

6. Penny Smith. Roseline Delisle. Ceramics Today. Reprint from Ceramics, Art and Perception. 27/03/2016. https://ceramicstoday.glazy.org/potw/delisle.html

7. Melanie Egan, Alan C. Elder, Jean Johnson. Crafting New Traditions: Canadian innovators and influences: University of Ottawa Press, 2008. pp. 25-9.

8. Danielle Turgeon. Un parcours en ligne droite. Août 2002. La Presse. La presse | BAnQ numérique

9. Frank Lloyd Gallery. Pasedena, CA. Further various catalogues.

10. The Marks Project. Roseline Delisle. https://www.themarksproject.org/marks/delisle

11. Roseline Delisle, Obituary. Los Angeles Times Chicago Tribune. November 16, 2003.

12. See item 20.

13. The Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center. “Kazimir Malevich, 1878-1935.”

14. Visual Diplomacy. Roseline Delisle. http://visualdiplomacy.blogspot.com/2011/12/roseline-delisle-quadruple-1988.html

15. ,Adrian Sassoon. Roseline Delisle. https://www.adriansassoon.com/artists/roseline-delisle/

16. Kristine McKenna Quoted in Var Roseline Delisle | Frank Lloyd’s blog. March 9, 2024. Roseline Delisle | Frank Lloyd’s blog

17. Brad Holland , Roseline Delisle. Creation No 6. nd.

18. Erin Aeschbacher. Milwaukee Art Museum Blog. Walkin’ in a Windhover Wonderland. December 5, 2019. https://blog.mam.org/2019/12/05/walkin-in-a-windhover-wonderland/

19. Triadic Ballet. Triadic Ballet at the University of California at Los Angeles, (UCLA Royce Hall) 1979.

20. Paul Mathieu. Profile: Roseline Delisle. Contact Magazine, Spring Issue Number 88. Alberta Potters’ Association 1992. pp.16-18.

21. Robin Hopper. The Ceramic Spectrum. Chilton Book Company, Radnir PA. 1984.

© November 2024 studioceramicscanada.com